Anaphylaxis — it’s a word that sends shivers down thousands of parents’ spines, not to mention child care workers who recognise the threat this major allergic reaction causes, particularly in children.

Every year, thousands of Australian children and adults are hospitalised for anaphylaxis, often a result of food allergies. In fact, according to the ABC, one in 20 children and about one in 50 adults suffer from food allergies – and so anaphylaxis has become a real threat.

Just in case you’re not clear on what anaphylaxis is, it’s the most extreme form of allergic reaction a person can have. It occurs when your immune system releases a flood of chemicals in response to an allergen (e.g. peanuts). Whilst we’ve already mentioned food allergies, other common anaphylaxis triggers include certain medicines, insect bites and stings as well as latex.

Anaphylaxis symptoms

Symptoms vary from mild – swelling of lips, face, eyes, hives, tingling mouth and abdominal pain – to more extreme (and potentially life-threatening) symptoms such as:

- Difficulty breathing

- Tongue swelling

- Tightness of throat

- Wheezing

- Dizziness and fainting

- Limpness (especially in young children)

Handling an anaphylactic reaction

Our child care courses and school age education courses prepare graduates to deal with a range of scenarios involving classroom emergencies, including anaphylaxis.

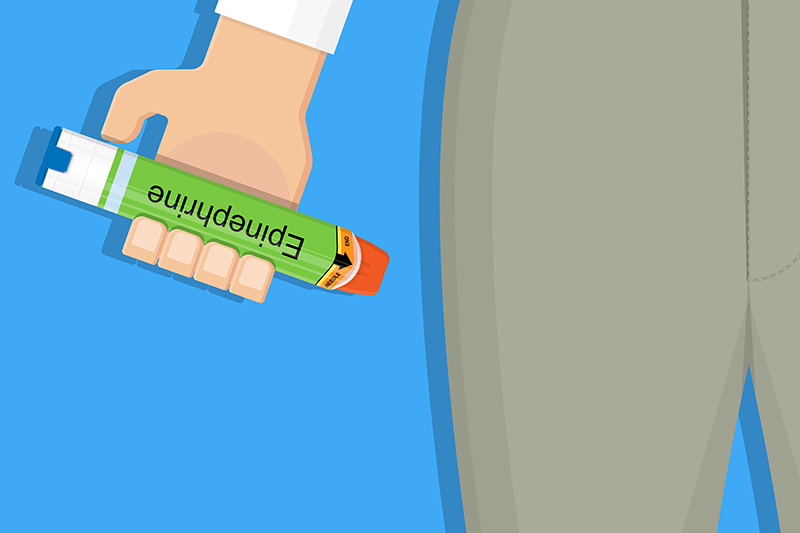

When children are having an anaphylaxis episode, they need a shot of adrenaline – a natural hormone in our body we need in plenty of supply to reverse the effects of anaphylaxis. Adrenaline is administered via an EpiPen — which is the only auto-injector we have containing adrenaline in Australia.

As a child care worker, you should have on record the children in your care who have allergies as well as available EpiPens in the case they need to be administered with adrenaline.

When a child presents with allergic reaction symptoms, it’s important to take them seriously and to monitor them in case they become worse. Research has uncovered that adolescents are more likely to die from anaphylaxis if they also have asthma, since symptoms of anaphylaxis (such as wheezing) can be mistaken for asthma. When these children/adolescents are given a puffer instead of an EpiPen, it creates a much higher risk.

Ultimately the best way to manage anaphylaxis is to minimise the risk of it occurring in the first place. Ensuring that children with known allergies are not exposed to allergens goes a long way to avoid emergency situations.

What else you need to know about first aid?

Book the course if your are ready